Thanks to the descendants of Ivie Callan who kindly agreed that we could reproduce the following Lecture delivered to Dalbeattie Library and Debating Society by Ivie A. Callan on Monday 11th November 1929. It gives a rare insight into Dalbeattie in the 1920s, as well as some very interesting snippets of history about the town.

The Lecture

Grey Dalbeattie Dear Dabeattie

Dark fir and sillar birk deck hill and howe

Loveland o’ mony a lass

Toasted in mony a glass

Hameland o’ mony a lad far frae thee now

So starts the chorus of a song written by a very old friend and collaborator of mine, Mr John Rae, and it, I think, makes a fitting introduction to my remarks tonight.

Set in a hollow of everlasting hills, and surrounded on all sides by eminences where the boughs of the oak, the ash, the beech, and the pendant branches of the birch line the pathways and the pine trees creep to the summit, Dalbeattie, if it can lay no claim to the possession of palatial buildings or to the higher graces of architecture, can at least lay claim to picturesque surroundings. Walking around it in any direction, the lover of Nature can find much to charm the eye and give food for thought.

On the Haugh Road one can look away up the long reaches of the valley of the Urr and see the far distant hills clothed in diaphanous garments of azure mist. Nearer, between the Mote and the foot of Barsoles, the river babbles and eddies into silent pools, where the foliage, the grass, and the flowers of its borders are mirrored as in glass. Standing above the watering-trough, and looking down, the river can be seen twisting and twining through pastures and meadows. It sleeps in deep pools, where the ash and the gean trees overhang them, and it babbles over noisy shallows by the ancient keep of Devorgilla and swirls into the stone pool at the scarred and weather-beaten face of Craignair. The Kirkennan Hills lie beyond; behind them the purple crowns of Screel and Bengairn arise against the sky, and far in the south the hills behind the Scaur are seen through a gossamer veil of vapour that hangs over the lower reaches of the river and spreads its shimmering folds over the Solway until it is lost in the pale blue haze that curtains the shadowy peaks of the Cumberland Hills. On the Moss Road are rugged moors and uncultivated wastelands blazing in Spring with the gold of the whins climbing up the declivities until they mingle with the heather that crawls to the summit, and in the long summer days burns with a purple fire on the crown of the Bienloch and the hills beyond it. From the Colvend Road the eye can take in the windings of the river Urr as it meanders through dewy pastures and daisy-spangled meadows at the feel of Kirkennan Hills, past the mansion house of Munches, half hidden among the sheltering foliage of old oaks and giant beeches that have basked in the summer suns and bowed their heads to the winter storms for centuries gone by. The view from the Dumfries road is not so expansive, but the walk past Edingham Loch to Culloch heights is invigorating and health-giving. All these views, however, can be obtained by taking the walk which skirts round the Rounall park.

Dalbeattie has other attributes such as that conveyed in an old local rhyme, the truth of which would be rash of me to dispute –in face, at least of the youth of the town.

Dalbeattie is a bonny place

Upon the Dubb o Hass

In it there’s mony a thrifty wife

Any mony a bonny lass

In contradistinction let me quote what the author of ‘East Galloway Sketches’ says:

‘To the strangest it must be confessed neither Dalbeattie nor it’s surroundings appear beautiful, and, judging from the rocky, barren-looking stunted protuberances which appear in nearly every direction, its immediate environs almost justify the local stigma that the country around shows it to be composed of the riddlings of creation’.

With that description, I think, none of my hearers will agree.

While the town from its first origin as a hamlet is less than a century and a half old, its name goes back by legend or tradition to early and stirring ages. There are not many documents extant that would throw light on its early history, but as far back as 1488 there is mentioned a family by the name of Riddick, proprietors of the estate of Dalbeattie, and in the book of the War Committee of Kirkcudbright on 2nd Sept 1640 Dalbeattie was ordered ‘to bring money for the baggage horse of the paroche of Urr’ but the requisition is presumed to have been upon the proprietor of the land since there was no town in existence. There is little doubt that the town derived its name from the designation of the farms which formerly occupied part of its site and surrounding lands. Timothy Pont’s map shows the present site of the town, near the junction of the Urr with its tributary Dalbeattie Burn, two farms: Meikle Dalbeattie on the left bank riverwards, and Little Dalbeattie on the opposite side; and, further up the bur the Mill of Dalbeattie. The farm names are now merged in town titles. Neither Dalbeattie – or, as Pont had it, Meikle Dalbeattie - on the left side of the burn, lies round about The Cross. The farm name still survives in that of Meikle Dalbeattie. It is also of interest to note from old documents that the Barr Hill was known in olden times as the village of Cunningham.

It would be difficult to form any correct conception of what the town was like in the early days, but it may be inferred that there were not many dwellings in it, and what few there were would doubtless be of primitive construction and covered with thatch. In 1858 the community had so increased that it blossomed out into a burgh. The movement towards this end was stimulated by the pressing necessity of more effective control over local affairs and closer attention to sanitary matters. Between 1840 and 1850 some alarm had been caused by cholera, typhoid and smallpox, but so far the only collective attempt to deal with matters of public health had been the appointment of a voluntary committee; but they had no expert knowledge of sanitation and no authority to enforce their recommendations, consequently it was deemed desirable to have the town declared a burgh and put under the regulations of the General Police Act. In 1861 the population, curiously enough, was 1861. In 1881 it had reached 3865, and it was estimated that the following year it exceeded 4000. The census return for 1921 was 2998.

Since its formation as a burgh, Dalbeattie has has 14 Provosts, the first being Mr T. Maxwell. Then followed John Carswell (three weeks), Dr McKnight, John Muir, Dr Lewis (17 years), Thomas Helm, Joseph Heughan, David McNish, George Shaw, William Davie, Dugald McLaurin, William Dornan, John Jack, Stuart H Doggart. Mr James Grieve was the first Town Clerk; Mr Jas. Little, the present occupant of the office, was appointed over 50 years ago.

I cannot go back to the days when the Noggie was a recognised scholastic institution, nor can I remember Sawny Watt’s hole at the Cross, ‘whaur the carlins dubbit their lint’, but before the days of the now defunct School Boards education was largely sectarian and under the direction of the churches. There were the Established Church school – or the Laich Kirk schule as it was called – the Free Kirk schule in Mill Street and some Adventure Schools, the principal one of which was Roland Atkin’s. After the advent of the School Board, the various schools (with the exception of St Peter’s) were all merged in the magnificent building on the banks of the Barr Burn, and the Jews had perforce to mingle with the Samarians. Making mention of the schools, one cannot help contrasting the school days of fifty years ago and the present time. Education then pertained strictly to school books. No attempts were made to turn us out into the world as carpenters or gardeners. We had no medical inspections to decide whether we were physically fit to jump the Lade. Our eyesight was not tested to ascertain whether we could find ‘crans’ in the bog; nor were our teeth examined to prove whether we were capable of masticating the ‘deserted village’ or the 2nd Paraphrase. Despite all these disadvantages – or, perhaps because of them – there was, I think, a greater love of letters then inculcated in the minds of scholars than the spoon-fed doses of the present curricula will ever achieve. That is purely a personal view and a digression.

While education was not neglected, there were not so many facilities for attending church as there are at the present time. At one time St Peter’s was the only church in the place, and those who did not attend that place of worship, went to the Parish church at Urr, and, if dissenters, they had to move further onto the Session Kirk at Hardgate. St Peter’s Church was built in 1813, the cost being defrayed by the fund left by Mrs Agnes Maxwell of Munches to the Catholic Church. The first minister was the Rev. Andrew Carruthers. Soon after the erection of the chapel, it is said, Mr Carruthers observed a man named Garmoury vigorously using a crowbar against one of the corners of the religious edifice, a canister of powder lying at his feet. Garmoury had been at a Whig preaching at the Haugh, where the Church of Rome was denounced as the Scarlet Woman and the Whore of Babylon, and woes threatened against those who tolerated her in the land. ‘What are ye doing, John?’ asked Mr Carruthers. ‘Oh’ he replied, ‘I find it is my duty to destroy the Church of Rome, and I’m gaun to begin here’. Mr Carruthers, who knew his man, quietly remarked: ‘I doot, John, ye hae a gey dreich job afore ye: will ye no be the better o’ a dram tae strengthen ye for your wark? Come awa to the hoose wi me’. John, nothing loathe, complied, and soon became so happy that he gave the powder to Mr Carruthers to shoot crows with and told him he had made up his mind to begin somewhere else.

Munches in Mr Carruthers’ time, was not the handsome granite mansion house of the present day, but was a long, mean looking erection of two low storeys with a rounded projection in front, and the Catholic chapel at one side. The congregation numbered about 130, but was in a state of confusion owing to the mismanagement of the former priest named Robertson, who, it is said, spoke several languages, having been a Government spy in foreign nations, and who had turned Protestant and remained in the neighbourhood. The Chaplain at Terregles reported that , in 1798, Robertson managed his congregation very oddly. A set of Elders (so called) formed his council respecting the poor; a set of lecturers and psalm readers spoke in the chapel on Sundays; and a Council met once a week at Dalbeattie to discuss points of faith and controversy. ‘He used’ the Chaplain reported ‘ to have singing and ranting psalms of his own translation, which I think most improper. Whoever succeeds him in the mission will have a hard task to set matters right again’. According to the writer of ‘East Galloway Sketches’ Robertson’s controversial Council was the forerunner of Dalbeattie Literary Society, the best of its class in Galloway.

Eventually, the usual orthodox churches were built – the Established, the Free, the U.P. and the Scottish Episcopal. In addition there was a church known as the ‘Morresonian’. There were also what the Sargeant Major called the ‘fancy religions’. You remember the story? The Sargeant Major at a church parade shouted, ‘Church of England men fall in to the right, Presbyterians fall in to the left, Roman Catholics fall in at the Centre; all fancy religions fall in opposite the – ah, er – bakehouse’. The Established Church in Burn Street – now the Armoury – was built in 1840, its first minister being the Rev James Mackenzie, who was ordained in 1843 shortly before the Disruption. It was during the Rev. John Mackie’s incumbency that the present church was built in 1880. Rev Mr Mackie caused a sensation in church one Sunday at service when he rebuked a member of the congregation exclaiming: ‘awake though sleeper. There is no sleeping in hell’. Correspondence ensued which the ‘culprit’ had printed in pamphlet form under the title ‘ The Sleeping Rebuke’ in which Mr Cuthbert stated that he laid his head on his arms because the preacher made such weird and unnatural faces when he spoke that it pained him to behold him. Rev James Mackenzie seceded from the Established Church, and formed a new congregation in connection with the Free Church of Scotland and a church was built in Mill Street. Rev George Dudgeon succeeded Mr Mackenzie, and was followed by Rev Robert Wright and Rev James Paton, under the latter of whom the Church was rebuilt in 1882 at a cost of £2,300.

The attempt to introduce a ‘kist o’ whustles’ into the church at Hardgate is said to have been the cause for the building of the U.P. Church in John Street. During the ministry of the Rev James Black a ‘band’ or choir had been introduced as a help in the service of praise. Though constrained to tolerate it while he was with them, some of the members had taken strong exception to it from the beginning, and on his removal they approached the Presbytery of Dumfries and obtained an Order for its discontinuance. Those who supported the innovation belonged to the lower end of the Parish and it was not long till steps were initiated for the erection of another church. While the church was being erected, services were held in the Commercial Hall, the Rev David Kinnear being elected Pastor in 1859. The church was built in 1861 and cost £1,000. In 1895 Mr Kinnear was elected to the Moderator’s Chair.

In 1866 Mount Zion Church was built, the first minister being Rev John Inglis, and during his pastorate, a manse and a small schoolhouse were built.

Before these days, however, there resided at Rosebank, a peripatetic preacher, the Rev John Osborne, who preached throughout the Stewartry for 20 years, but was deposed for preaching Arminian doctrine, and for other offences. One of the charges was that, instead of attending the funeral of one of his leading followers in Auchencairn, he went off to visit a Rascarrel acquaintance, forgetting the more important event. Meeting one of his former elders some months after his deposition, he enquired why his place had not been filled up. ‘Oh’ replied the Elder, ‘we have never yet been unanimous whom to elect.’ ‘You could be unanimous enough’ replied Mr Osborne ‘when you wanted to get rid of me’. It was the same Mr Osborne who said it required an angel or a jackass to preach to the people of Dalbeattie, for the one could live on nothing and the other on thistles.

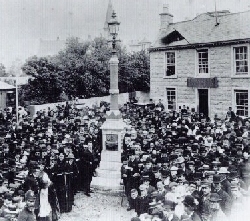

There was a plethora of public houses in those primitive days. The Plough Inn was in the house now occupied by Mr A Crosbie and on the opposite side of the Cross was The Brown Cow. The Commercial Hotel was once The Kings Arms, and the landlady at the Maxwell Arms kept the Post Office in a room next to where the Commercial Room is now. There were many other licensed places, a list of which was once given me by the late Mr McKinnell, for many years ‘father’ of the local lodge of Freemasons; but the list has gone astray, and the sites would not be easily determined now. It cannot be said what the average gains of these ancient hostels were, but it is stated that they all did a roaring trade when Dalbeattie Fair was a lively and thriving institution – when the Cross was covered with shows and thimble-riggers, and farmers with their wives and sons and daughters, the cotters and their servants dressed in their Sunday claes, made the High Street almost impassable from McLaurin’s corner to the doors of the public houses ower the burn. Michael Henry then catered for the wants of the community by making a pilgrimage through the town stocked with snap-men and ‘rabbits frae Hestan’. His one temperance sermon was that ‘a man had no more need for whisky than a duck had for an umbrella on a rainy day’.

The number and character of lodging houses in the town in those early days was a source of trouble. These were largely occupied by sturdy beggars or vagrants of a dangerous type. Complaints were laid before the Kirk Session, and three elders were commissioned to enquire into the way in which these lodging houses were conducted. The report throws such light upon the characteristics of the time that part of it may be quoted:- ‘Some of the houses are kept in a most disorderly and profligate manner; each and all of them are the receptacle of drunkards and vagabonds, the very off-scourings of society; drink is brought into these houses (for they are below the character of obtaining licences) when the poor unthinking wretches get abominably intoxicated, and every species of sin and wretchedness is committed’. The Session directed the Clerk to furnish the Factor on the Estate on which these houses were situated with a copy of this report, ‘that if possible according to a laudable proposal of Mr Copeland of Colliston, a stop might be put to such sinful practices’.

At one time there were only two or three Drapers, two or three grocers, one baker and one butcher in the town. The first drapery establishment of any pretensions was opened in 1832 by Mr Thomas Rawline in the shop now occupied by Mr John McKie. The baker’s shop was in the corner shop opposite the Union Bank, and in 1840 was run by Mr David Paterson, whose grandson still continues the business. The butcher’s shop was in the same vicinity. Banks were a thing unknown, and, mayhap, undreamt of. A lady commenting on these things once said: ‘Ye see there were nae banks then for we jist borrowed and lent amang ain anither an’ werna a hair waur aff than we ir noo’. Banks came, however, the advent of the Union Bank taking place in 1852. The Commercial Bank was established in 1889 and the Clydesdale Bank in 1910. By the time Dalbeattie came to have its bank, its postal correspondence had largely increased from the days when it could be manipulated in a room in the Maxwell Arms Hotel. In view of the cost of the transmission of letters, it may well be believed that there would be no great strain on the service of the post office in the earlier days. Isabella Watson, in the story of her life, a local pamphlet published in 1835, informs us that she paid £1 sterling to John McNish, Postmaster in Dalbeattie, for some letters she received from him, one alone – a rather bulky packet costing her 8s 9d. Yet we grumble nowadays that we have not got the Penny Post! The Post Office was afterwards in a shop in High Street (probably Miss Craig’s) and was later removed to the house now occupied by Mr Shackley in Maxwell Street. Later it was transferred to the Town Hall buildings, and from there to its present habitation.

For a number of years a family named Milligan had a woollen mill, which was later turned into a granite polishing yard. Five other mills were at this time in operation in Dalbeattie:- the Paper Mill which was first in the hands of a man named Cochtrie, later by William Lewis, and for 37 years by Mr John Forsyth; a grain mill in Craignair Street occupied by Anthony Broadfoot; a walkmill established by Hugh Lindsay at Islecroft in 1801; two mills for sawing wood. There was also the famous bacon curing establishment carried on by Mr James McLaurin which was given up 55 years ago. The business of grain millers and merchants now carried on by John Carswell and Sons at Barrbridge Mills was established in 1837. Three years later, Thomas Biggar commenced to lay the foundation of the trade and farm seeds and artificial manures. William Elliot had been in business as a blacksmith at Islecroft from 1821, and about the year 1835 his son John built the forge at Maidenholm for the manufacture of reaping hooks. When the scythe began to supercede the reaping hook he effected such changes in his work as enabled him to produce forgings of a larger kind. In 1845 Messrs Helm established themselves on the banks of Dalbeattie burn as wood merchants and bobbin turners. The business was afterwards transferred to Messrs Jackson, and a relative of the latter still carries it on at Islecroft. At this period there were no houses in John Street, Station Road , or Craignair Street, saving in the latter a small cottage fenced in, with a garden before the door and known as Dykeside. Its site was about No 4 in that street.

In 1855 Dalbeattie Agriculture Society was formed for the purpose of promoting an annual exhibition of the farm stock and produce of the neighbourhood. The Society still continues in existence, and has maintained its annual show with great regularity, previously only giving way every 5 years to the Dumfries Union and at longer intervals to the Highland Society when their exhibition was held in Dumfries.

In the year 1859 Dalbeattie Gas Company was formed and the town illuminated with gas, being the first of the villages in the south to take this step. The price of gas in 1859 was 12s6d and once was as low as 5/- per 1000; now 9s2d. And it is interesting to note that the Town Council of the Granite Borough was the first Council in Galloway and is still the only one – if we except the Burgh of Maxwelltown – to adopt electricity for street lighting. In the same year (1859) the advent of the railway was a boon to the inhabitants, and gave a decided impetus to trade in the District, which was, even before that time, rapidly increasing. A local scribe (whim I cannot identify) may be forgiven for perpetrating the following verses in the exuberance of his joy that at last the Auld Toon had come well within the pale of civilisation:-

The Engine is coming huzza huzza ; The steamer is coming huzza huzza!

The Engine is coming, the carriages running, and visitors coming so gay, so gay;

Then come to the station today, today: then come to the Station away, away;

Then come to the station without hesitation, and join in the welcome huzza, huzza.

The folks frae Dumfries will be braw, be braw, the Maxwelltown gentry a’n a’, an’ a’;

The folk frae Kirkgunzeon some riding some runnin’, Kirkbean and New Abbey an’ a’, an’ a’.

Colvend and Dalbeattie will pour, will pour, their folk frae the Water o’ Orr, o’ Orr.

We may look for some men and women, I ken, who seldom came near us before, before.

An’some frae Kirkcudbright will come, will come, an’ Balmaghie folk frae their home, their home;

The country a’ roon’ will come to oor toon like troops at the sound of the drum, the drum.

Then let us be kind to them a’, them a’ , an’ busk up our station sae braw, sae braw.

Wi’ music so sweet our friends let us greet, and give them a hearty huzza, huzza!

The late Mr Maxwell of Munches, it may be added, was Chairman of the company that constructed the line and on the completion of the undertaking gave a free run to Glasgow to the workmen who had been employed upon it. It is recorded that one of the excursionists is said to have refused to leave the station in Glasgow to see the sights in case the train would set off on the return journey without him.

Previous to the introduction of the railway, traffic was dependent on horse carriage, and the only means of travel available, apart from private vehicles (which were few) and horseback (which was mostly favoured by the farmers) was the comparatively slow-going stagecoach, a heavy covered conveyance with some outside seats behind and above. Journeys to Dumfries were by stagecoaches, between two of which – the Perseverance and the Victoria – there was healthy rivalry for a considerable period, the former having the suffrages of the Dalbeattie boys, who displayed their enthusiasm by meeting her on the Dumfries road with some semblances of flags on poles, and cheered with all the strength of their lungs, while they groaned and hissed at her opponent. The only semblance of the old coaching system which persisted until a few years ago was the Mail gig which left Dalbeattie every morning.

Coals were all brought from England by sloops owned by John Shaw, a retired blacksmith, who lived in Water Street ; John Sloan, Nathan Copland and others. Some of these vessels were built on Dalbeattie Burn at the Port. One of them was the Elizabeth and Ann, but perhaps better known by her nickname: ‘God’s Curse’ – of which Charles Clachrie was the master. At the launching ceremony the gentleman who was performing the principal part slipped his foot and dropped the bottle with which the christening ought to have been done. Instead of naming the vessel he emitted a hearty curse, and from this fact popular humour conferred upon it the designation by which it was afterwards known. In those days it was no unusual thing to see a line of carts on the Haugh Road filled with coals and other merchandise for the Haugh of Urr and other landward villages.

I suppose Dalbeattie in its earliest days would have its worthies – people who by their idiosyncrasies and little mannerisms distinguished themselves from others – but I can find no trace of any. Fifty years ago, however, there were quite a number. Among them was Dolly McKune, maker of treacle toffee and treacle beer, to whom we took our old copy books, the sheets of which she used for wrapping up the purchases of toffee and in exchange for which she gave us a morsel. Then there was Herrin’ Mary, who hawked herring round the town. ‘By a wheen mistress,’ she would say, ‘there’s nae need o’ gravy in the pan; they’re that fat they fry themsels.’ Among the men were Nathan Major, the carrier to Dumfries: Robbie Johnstone, the blacksmith, who drove to his work at the Hill in his own carriage drawn by a cuddy: and Johnny Caven, the bellman. Johnny for a time looked after the Commercial Hall, and was once once asked to sweep out and clean the hall and ‘bell the toon’ for a meeting. He wanted 7/6 badly, but could not sufficient items to make up that amount, so he simply added to the account : ‘to bother and fash 2/6’. Michael Henry, to whom I have already referred, was another worthy. So was Bob Dickson, who would be one of the last post-boys – that is one of those who had ridden postillion. So were ‘sober John’, a tailor, who was drowned in the Mill dam: and Johnny Muir of the Commercial Hotel. Bonar and Riley were a great pair. Both kept a lodging house, both sold crockery, and both were fruit merchants. Those were their points of similarity. Physically Bonar was a large man: but Reilly was a perfect shrimp in size. But Mrs Riley made up for that, for she was a fine bouncing lady. On the other hand, Mrs Bonar was the antithesis of her lord (but not her master) being a very thin woman. Many of you, of course, will remember Bolton Willie. He had, perhaps, a slight ‘want’, but in a general way he knew how many coppers went into a sixpence. A few days ago I came across some verses, which explain the origin of his nickname. The first verse runs:-

A weel kenned face in oor auld granite toon

Is the face o’ oor frien’ Bolton Wullie,

He was kenned by us a’ for miles far aroon’

And he kent every ain, Bolton Wullie

His mither puir body, frae Da’beattie ae day

On business or pleasure to Bolton did stray:

‘She’ll bring me some bools,’ said Willie, ‘hurray’

And earned there and then his soubriquet:

‘Bolton Bools’ first, and then ‘Bolton Wullie’

Then there was the red headed ragman from the Ferry Toon o’ Cree – Jamie Hughes. He was Irish, and his failing often led him into conflict with the law. Once, referring to Dr Lewis, the chief magistrate, he said: ‘He’s a guid man, the doctor, but a wee bit hard on the like o’ me. Noo, if a was the doctor, and he was the red-headed ragman, I wad say: ‘behave yersel, Jamie, when ye get a wee Donal’ ; but fourteen days up by is salt enough’. ‘A wee Donal’ was Jamie’s euphemistic way of describing a full dress parade when it had taken all the strength of the available police to remove him to Durance Vile. Jamie, when sober, was a likeable chap, and it is written that

For rags and bones and dulcet tones

Full faitly pleaded he

And then began for rabbit skins

To cry most earnestly

We liked him weel, the same auld chiel

And we will e’er refuse

To think he’d no get a cosy biel

The weel kent Jamie Hughes

A lecture on Dalbeattie would be incomplete without reference to the staple industry. (I might hear remark that I never hear the words ‘staple industry’ without being reminded of a visit which I once paid to Ireland. When in Draperstown, which is no mean village, I enquired of our jarvie, as there was scarcely a soul tobe seen on the streets, what the staple industry was. ‘I beg yer pardon, sir,’ he said. I repeated the question, and getting a like reply I put it in another form and asked what the public worked at. ‘Ach, sure sor’ was the reply ‘they don’t work; they’re all farmers’)

We live by our staple industry. The demand for granite affects the prosperity of Dalbeattie and to a great extent controls its population and our creature comforts. It is not with any degree of certainty that the actual date of the commencement of the granite industry can be stated, for it gradually grew from the gathering of boulders in the district. There could hardly have been quarries in Dalbeattie 132 years ago, else the contractors would not have gone to Kirkgunzeon for stone for the building of Buittle bridge. The Mersey Dock and Harbour Board are credited with giving the first impetus about the year 1820, and were the first to ‘tap’ Craignair. For twelve or thirteen years they took rock from this source, but after a dispute with the landlord they left and went to Creetown. After 1831 these quarries lay idle for some time, but eventually were taken in hand by Messrs Andrew Newall, Anderson, and John Shaw, who started in partnership. A difference arose among them over some trivial matter, and the disputants had recourse to law, and again there was a cessation of work. The earliest recorded date of some business done was in 1821, when Mr Maxwell of Munches gave a certificate order for a pair of granite gateposts; while it is recorded that on the 17th March 1828, Mr Andrew Newall paid the proprietor for twenty six and a half tons of granite at 1/- per ton. This, it is presumed, was mostly gathered anywhere on the estate. The granite for Mr Maxwell’s momument was gathered where it could be got suitable for the purpose. Mr Hugh Shearer took over the quarries vacated by the Mersey Dock Board, but the date is again indefinite. In 1865, however, it is known that Messrs Shearer, Curteis and Co. employed a large staff of workmen and had quarries at Granhill, Old Land and Craignair. It is to this form that the credit of opening nearly all the small quarries in the neighbourhood is due. A portion of the granite used for the Thames Embankment was taken from the Old Land Quarry. In 1870 the constitution of the firm underwent a change, and for 5 years traded as Shearer, Smith and Co. In 1875 another change took place, when Mr Field succeeded Mr Smith. Only one year, however, did the business pay the firm and the state of affairs when the statutory oath was administered in 1883 showed: Assets £14,319.14s.9d; Liabilities £15021.3s 6d – a deficiency of £701.8s9d. With the exit of this firm the granite industry reached very low ebb and, with the object of putting a sprag on the wheel of Depression, a meeting of gentlemen interested in the welfare of the town was held to consider the desirability of taking over the quarries worked by the bankrupt firm. A sum of £1500 was subscribed at the meeting, but the scheme was ultimately abandoned on the ground that the facilities offered by the proprietor were not such as to give much hope of floating a company successfully. In 1886 Mr Thomas Parker floated a company with a capital of £25,000 to work Lotus and Barnbarroch quarries. The prospectus stated that it was not expected that more than 10/- off the £1 shares would be called up, the Directors considering that that amount would be ample to support the anticipated extension of the business of the company. The profits were expected to be not less than 15% per annum, which, saif the prospectus ‘is considered a small profit in the trade’. But they never saw a dividend.

The Newalls started their business about the same time as those I have mentioned – at Craigmath, Barrhill, Old Land, Newabbey and later at Craignair. The only tool then in use was called the ‘tearing pick’ which weighed from 15lbs to 20lbs. In cutting the stone the method was to strike with the pick until an indentation was made, and then insert a wedge. In this manner the rock was torn asunder. Dressing was also executed with the pick. Two clean-axed gateposts at Craigmath, executed by Andrew Newall, were considered a marvel of workmanship, and visitors came from far and near to see them. The idea that mouldings or fancy work could be executed in granite was generally scouted, although a finer class of work was introduced with the single axe. The first building in Dalbeattie in which this axed work was introduced was in the erection of the Parochial School in the High Street. Wages in those times were from 1/- to 1/3 per day, and 2/6 for masons. The man who earned a guinea a week occupied a very enviable position. The people lived on oatmeal – when they could get it – for it cost in dry seasons from 5/- to 6/- a stone (17 ½ pounds to stone) – and potatoes, which could be obtained at 1/- a cwt. In the year of the short corn the latter edible was the staple food, and the menu was: breakfast, potatoes; dinner, potatoes; supper, potatoes. Butcher meat was an undreamt of luxury and was not to be seen inside a workman’s dwelling. It was many years later before it was possible to buy meat, and even then it was a rarity for the consumption in the town did not exceed one sheep per month. A story is told of a rather amusing incident in connection with one of Dalbeattie’s first butchers. One of the butcher’s customers died and an account was rendered to the brother of the deceased for meat supplied. No notice was taken of this, as a receipt was found among the deceased’s papers. Sometime later another account was submitted, with the additional item of two sheeps’ heads. This greatly astonished the brother who ejaculated, ‘fore God, is oor Rab eating sheeps’ heids yet!’

Blasting operations were carried out in a very crude fashion compared with the elaborate preparations of the present day. Accidents were of almost weekly occurrence, and in the early days of the Newall history, Homer Newall and three workmen lost their lives. Cranes were then unknown, and the loading of carts and vessels could not be characterised a labour of love. Stones were carted to Kirkclaugh, near Munches, where there was a Quay. The first attempt to polish granite was made in 1834, and the stone is in the possession of Mrs James Newall, John Street , Dalbeattie. It was polished by Andrew Newall on a free stone flag. In 1841 a memorial stone for the late Dr Lewis’ uncle was executed in a shed at Craignair. The polishing was all done by hand with a plane-shaped box hollowed in the side then filled with sand. In 1851 another stone was polished, also by hand, on which was incised a Scotch thistle. This stone found its way to the Exhibition held in London in that year, and received prominent notices in the Press.

With Dalbeattie lies the honour of first introducing as a business the crushing of stone for granolithic paving. Like all other branches of the granite industry, it had a small beginning. Messrs Shearer, Smith and Co were the first to erect a crusher, but previous to that they had men employed riddling the sett makers’ chips.

In imagination we can picture the great advances made from those days until the erection of George V Bridge in Glasgow, and it is only natural when we think of the works of architectural beauty and the skilfully executed sculpture work of our granite craftsmen, that we should be proud of our granite. Craignair will never be allowed to fade from our memory. Even should it do so for a time, some building or monument will meet our gaze to awaken and refresh us. The Great Little Bass Lighthouses (Ceylon) shed their beacon lights over the Indian Ocean and furious cyclones beat with fury against their solid structures of Dalbeattie granite. The billows of the Atlantic hurl themselves against Eddystone Lighthouse, and there the same material bids defiance to their almost resistless charge. Stately ships sail in and out of the harbour of Trinidad, the old Stanley Dock in Liverpool, and numerous docks and harbours throughout the United Kingdom, or find safe refuge therein, sheltered by the solid masonry from the same old hill. The rock from its bosom has taken its place, among others, in beautifying the Thames Embankment. Its polished brightness embellishes the frontage of many a bank and office and public building; and endless traffic is carried on, and millions of people pass daily over, the hardy material abstracted from her sides to form the highways and cover pavements of numberless cities and towns throughout these realms. In contrast to the stirring and stormy use for which our native granite is adapted and adopted, many beautiful memorials selected from the same prolific source, have been reared throughout this and other lands. It has been used to commemorate the virtues and bravery of not a few of the nation’s heroes, amongst them Lord Nelson, General Gordon, General Neill, as well as memorials to those who fell in the Great War. Dukes, earls and statesmen have chosen it to adorn their last resting place, and the lovers of Shakespeare and our beloved Burns have not been behind in acknowledging its beauty and worth. Travellers will find it in America, in Africa, in Ceylon, in Australia, and in many parts of the European continent, and even in the little town of Tiberias it stands proudly overlooking the blue waves which roll nightly o’er deep Galilee. Well might we unite in singing the praises of this grand old hill in the words of Sprout:

Then let us join at Nature’s shrine

And breathe our earnest prayer

That though she gave no golden mine

She blessed us with Craignair

The motto of Dalbeattie is ‘Respite: Prospect’ (looking backwards: looking forward ). Looking backward, we learn that Dalbeattie was the first town in the Stewart to have its own gravitation water supply, and was also the first to introduce draining. Dalbeattie was the first town in the county (if we except Maxwelltown which was then really the Brig-en o’ Dumfries ) to have its streets lit with gas. Dalbeattie Council was also the first Council in Galloway to adopt electricity for street lighting. The first agricultural show in the Stewartry was held in Dalbeattie. Stone for granolithic work was first crushed in Dalbeattie. Granite was first polished in Dalbeattie. Dalbeattie was the first town in the County to have some of its streets paved in the most improved manner. Is not this a heritage to be proud of? Can we be accused of egoism if we subscribe sincerely to the toast: ‘Here’s tae us; Wha’s like us?’ With such a record behind us, we look confidently forward to the future, in the assurance that those who follow will honourably uphold the great traditions of the past, and maintain Dalbeattie’s reputation of being one of the most progressive of the small burghs of Scotland.

‘When simmer sun sinks ‘neath the broo’ o Buittle’s westling braes

An’ auld Da’mun, bared by the win’, stands tinged wi’ gloamin’ greys

Then memory mingles wi’ the sicht, as fit words wi’ a tune

An’ gowden glints o’ glory licht on auld Da’bettie toon’.